This is a slow-brewing documentary and Taiwanese director, Yao Hung-yi (姚宏易) clearly shares a love of long but poignant camera shots with executive director Hou Hsiao-hsien (侯孝賢). The documentary is about Chinese artist and actor Liu Xiaodong (劉小東) going back to his hometown of Jincheng in China’s north-western Liaoning province to paint his childhood friends. Liu was a producer on Devils On the Doorstep, which I reviewed here, and starred in the film The Days (《冬春的日子》), which I haven’t yet seen.

This is a slow-brewing documentary and Taiwanese director, Yao Hung-yi (姚宏易) clearly shares a love of long but poignant camera shots with executive director Hou Hsiao-hsien (侯孝賢). The documentary is about Chinese artist and actor Liu Xiaodong (劉小東) going back to his hometown of Jincheng in China’s north-western Liaoning province to paint his childhood friends. Liu was a producer on Devils On the Doorstep, which I reviewed here, and starred in the film The Days (《冬春的日子》), which I haven’t yet seen.

Monthly Archives: January 2015

Mona Rudao (莫那魯道) Commemorated on NT$20 pieces

Mona Rudao, the chief of Seediq tribe during the Wushe incident – a rebellion against Japanese rule which ended in a violent crackdown and Rudao’s suicide, has been commemorated on a NT$20 piece that I was handed at a restaurant yesterday. Continue reading

Mona Rudao, the chief of Seediq tribe during the Wushe incident – a rebellion against Japanese rule which ended in a violent crackdown and Rudao’s suicide, has been commemorated on a NT$20 piece that I was handed at a restaurant yesterday. Continue reading

Shamelessly ashamed: 「不恥」 or 「不齒」Homonyms and Antonyms, or are they?

I came across this phrase is a translation I’ve been working on:

他因為自己是騙子,所以對那些以扒竊、順手摸、甚至搶了就跑的行徑為生的族類自然是不恥的[……]

Amusingly Honest Store Sign Celebrating Betel Nut Addiction 戒不好檳榔

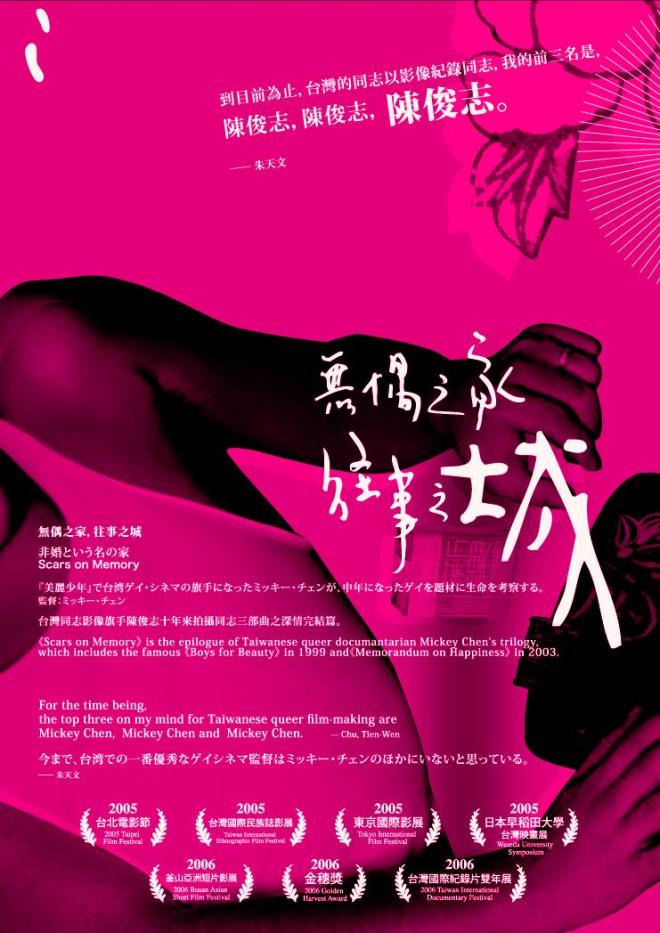

Review of ‘Scars on Memory’ a documentary by Mickey Chen 陳俊志的《無偶之家,往事之城》 影評

The Chinese title of this documentary translates literally to “A home without a spouse, the city of the past.” It is directed by Mickey Chen (陳俊志), who wrote quite a biographical book Taipei Dad, New York Mom (《台北爸爸紐約媽媽》) a few years ago. I’m halfway through it, but I would recommend what I’ve read so far – as it is a touching account of a gay man’s life without being trite or shmaltzy. Continue reading

The Chinese title of this documentary translates literally to “A home without a spouse, the city of the past.” It is directed by Mickey Chen (陳俊志), who wrote quite a biographical book Taipei Dad, New York Mom (《台北爸爸紐約媽媽》) a few years ago. I’m halfway through it, but I would recommend what I’ve read so far – as it is a touching account of a gay man’s life without being trite or shmaltzy. Continue reading

A legless night in Taipei! – The font that made 夜 lose its left leg

I found this version of 夜 in Roan Ching-yue’s 《哭泣哭泣城》 The Sobbing City, from which I translated ‘The Pretty Boy from Hanoi’ in a previous post:

Does anyone know what font this is? All the fonts I have on my computer have both their legs – I like the elegance of this form of 夜 though. Anybody familiar with it? Comment below.

By the way, I’m planning a few more translations from this collection of short stories, so look out for them over the coming months.

For Chinese font watchers, I recently came across this book in a Taipei book store.

I had a little flick through – though budget constraints prevented me from buying it yet. From what I saw it explains variations in the use of font in shop, road and MRT signs, looks to be an interesting read.

Dafont has some additional Chinese fonts for those interested.

Guest post: Garrett Dee on Jia Zhangke’s ‘A Touch of Sin’

This is a guest post from blogger Garrett Dee which offers a different perspective on a film I reviewed a little while ago, Jia Zhangke’s A Touch of Sin. Check out Garrett’s blog here.

Devoid of musical background and utilizing the now smog-covered skies over much of China as its primary color scheme, Jia Zhangke’s most recent film A Touch of Sin presents to the viewer an aggressive portrayal of modern China in which the average citizen fights a sometimes life-or-death struggle for their societal niche. Spanning a series of four short vignettes, each focusing on a single character and based (partially) on real-life events, Jia’s engaging film seems meant to be viewed as a loosely-fantastical interpretation of a Middle Kingdom in which what has been thought of as a traditionally communal society has become atomized by wealth, power, and frustration.

It is the casual method with which Jia peppers the plot with violence, which is neither discussed or lingered upon for too long a frame, that appears more crucial than the violence itself. I am reminded in a way of the titular character of the novel American Psycho, who intersperses his daily routine with random acts of murder in such a nonchalant way: a killing of a homeless man during a coffee break here, murdering a prostitute before going to a nightclub there, and so on.

Jia’s film’s violence, however, seems to want so say something about his homeland in that very circumspect way that many Chinese artists (see, Mo Yan and company) seem to have perfected given the limitations under which they labor. In most of the vignettes, the characters are only driven to violence after suffering some sort of injustice. This seems in part, though, due to the ubiquity with which violence is dealt out in Jia’s China, the young woman in particular suffering through several bouts of violence with no visible reaction from onlookers, who have no apparent qualms about a woman being forcefully thrown against a car and wandering into an inexplicably unattended snake pit.

The exception to this theme of flight from some kind of persecution seems to be the second vignette, the story of the young man returning to his family village to celebrate his mother’s birthday before murdering a woman and bystander in order to steal the woman’s purse. Based on the factual incident of Zhou Kehua, a gunman suspected of murdering nine people before he was finally gunned down by Chinese police in 2012, his acts of brutality appear to be somewhat cathartic, a symptom of the same restlessness that has driven him from city to city in such a driftless manner.

Indeed, this listless mobility weaves into the narrative throughout the final three vignettes and seemed to be one of the strongest unifying themes of the film as a whole. The characters seem to have little compunction against abandoning their place of abode for somewhere new, whether out of necessity or, in the case of the Zhou character, for the sheer desire to be an abandoner of past and family in favor of something new. China is indeed undergoing the largest mass migration in human history, and the way in which these characters constantly reshuffle their lives around jobs and lovers, alighting at their family homes before departing for parts unknown, seems realistic when set in this context.

The order in which Jia chose to place each of these vignettes appears to form a kind of meta-narrative, descending from the high vantage point of characters who proactively seek redress and agency towards a state of utter hopelessness in the face of a bleak future, driving them towards either death or a profound detachment. The final scene, in which the young woman, who we last see as having cut her hair short and fabricated a new identity, stumbling aimlessly through the barren landscape before joining a crowd of blank faces gazing at a puppet show ends the film on a hollow, bitter note.

This is, after all, Jia’s puppet show, one in which he cruelly dangles his marionettes in agony before cutting their strings and smashing them on the ground. In Jia’s version of China, though, the real puppeteers seem to be the most wealthy and powerful, whose fortunes and statuses allow them to not only afford lavish lifestyles in significant disparity from the meager existence of the various protagonists, but also permit them to do as they please with impunity. However, the initial vignette, is an answer to this problem, a fantasy in the style of the 2011 film God Bless America in which Jia gets to have some darkly humorous fun of his own as his protagonist sets about literally blowing the heads off of those who have wronged him.

Jia’s fascinating film serves his homeland up to audiences as a cynical, lawless society in which violence permeates daily life and wealth is the only respected authority until it annulled at the barrel of a gun or the edge of a knife. Jia stays away from explicit criticism of the policies that have led to this sort of situation, but the implications of the desperation and restlessness with which he portrays the lives of his main characters suggest these are but a microcosm of problems on a macro scale.